Thomas A. Ferrara/Newsday RM via Getty Images

- The not-quite-urban, not-quite-rural "exurbs" are booming in popularity after the pandemic.

- The pandemic-era shift from a daily to a weekly commute made them suddenly viable.

- It's early, but city dwellers' migration to exurbs resembles the suburban boom of the 1950s.

- See more stories on Insider's business page.

In the 1950s, Americans left densely packed cities for a new kind of neighborhood amid a housing boom: the suburbs. Today, a similar shift is under way for a new kind of neighborhood: the exurb.

If the term doesn't ring a bell, that's the point. Exurbs only just started to gain popularity in recent years for their combination of cheap housing, greater space, and being a still-commutable distance to a city.

Of course, it's hard to define the exurbs as the "new suburbs" when suburbia itself lacks a commonly accepted definition, as Insider's Juliana Kaplan reported. But Americans should get used to them: They're the new endpoint for the latest iteration of the American Dream.

Exurbs and emerging suburbs have both grown faster than cities over the past two decades, but the coronavirus pandemic changed that, stalling suburban growth and throwing urban areas in decline while setting the exurbs up as the big winner.

The end of the commute fueled the rise of the exurb

Brookings defines exurbs as communities "located on the urban fringe that have at least 20% of their workers commuting to jobs in an urbanized area, exhibit low housing density, and have relatively high population growth." That applies to a wide range of rural areas, especially in a reshaped economy in which commuting has taken on new meaning.

The end of office-based work was the impetus, and city dwellers accustomed to daily commutes and cramped apartments rushed to exurban locales outside Jacksonville, Florida, San Antonio, Texas, and Charlotte, North Carolina.

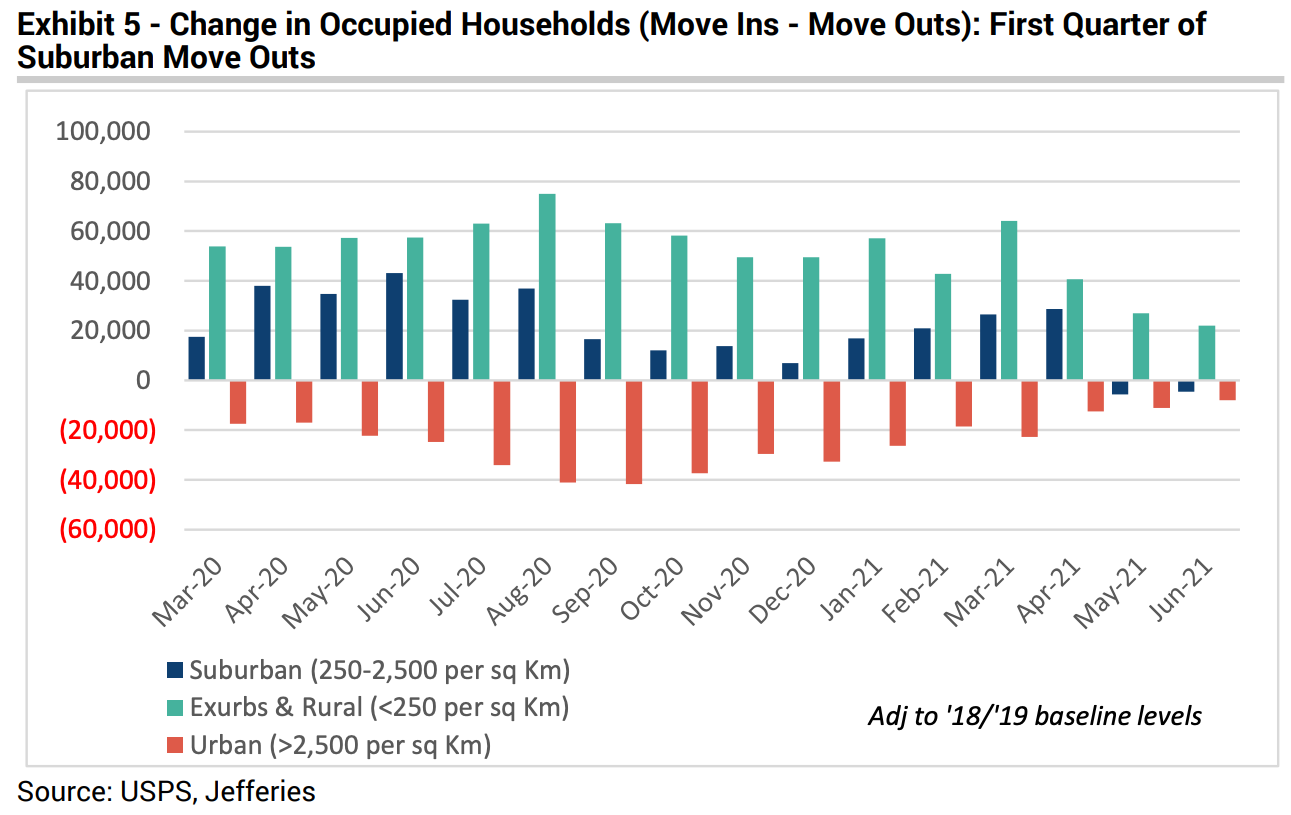

While much of the country has now reopened, the city-to-exurb migration is alive and well. Occupancy in exurbs continued to climb in May and June by more than 20,000 people each month, while both months saw Americans exit cities and suburbs.

"Instead of thinking about the daily commute, it's going to be the case that renters and homebuyers are going to be thinking about the weekly commute," Robert Dietz, chief economist at the National Association of Home Builders, told Insider. "That does expand the geographic area in which they can choose where to live and gives them some additional buying power."

The share of Americans working remotely before the crisis sat in the low single digits, but it's expected to normalize at 30% once the pandemic fades, Dietz added.

Jefferies

That expansion has already shown up in early indicators. Jefferies economists said, citing USPS mail-forwarding data, said areas around Raleigh and Cary, North Carolina, saw some of the largest increases. And while the Los Angeles metropolitan area shed residents, neighborhoods near Riverside and San Bernardino grew.

The exurban boom is the answer to the question of the last year's historic surge in home prices. Simply put, the number of viable destinations has expanded because of a different economy, and the prices have shot up as everyone wants their slice of the exurban dream - especially in exurbs.

The exurban boom as a byproduct of 2020's housing crisis

Of course, the other reason the exurbs are popular is America's historic housing shortage.

The pandemic housing boom quickly morphed into an inventory crisis, the result of contractors underbuilding over the past dozen years and a related shortage in lumber that dates back to the housing crisis of 2008. Builders simply need to ramp up home construction to meet demand, but in the meantime, prospective homebuyers are venturing farther and farther out.

A virtuous cycle of exurban moves and development could be the silver bullet to end the housing crisis, NAHB's Dietz said. The regions are perfect for building the single-family homes the country has a dire shortage of, and a meaningful increase in supply is "ultimately a way that we can protect housing affordability," he added.

The migration - deemed the "Great Reshuffling" by real estate giant Zillow - stands to flood the once-neglected regions with new wealth.

The trend echoes that of the suburban boom of the 1950s, which saw hordes of Americans populate new communities outside cities just after World War II. That exodus coincided with the postwar baby boom and the related rise of consumer culture. A variety of powerful economic forces during the 1950s made it relatively easy for mostly white citizens to realize what had become that time's version of the American Dream, signified by a nice house in the suburbs, with a yard and a picket fence. The modern version looks like a bigger yard, fewer neighbors, and a car that only makes the (long) commute into the city once a week.

The drivers between the migrations then and today are also similar, Dietz said. Just as the Greatest Generation in peak homebuying age powered that surge in suburban demand, millennials are at their peak homebuying age now. The generation first began reviving the exurbs back in 2019, sacrificing a shorter commute for more savings on a home, and the pandemic accelerated that preexisting trend. The future of the migration to the exurbs depends on whether that trend persists.

What's easily forgotten is that building more homes requires land, Ali Wolf, chief economist at homebuilding prop tech company, told Insider. "To see considerably more homebuilding over the next decade, builders will need to find infill opportunities for redevelopment, move further to the outskirts, or start additional building in parts of the country with more developable land," she said.

That might mean building more homes out in the exurbs. "As more homes are built further from downtown, buyers can expect that suburban amenities will improve, creating new gathering places and hotspots," she added.

But for the cycle to begin, the migration needs to stick. Areas far from cities become the hardest to develop when housing demand drops, Wolf said. The exurban revolution, then, is in the hands of the movers.

"It all comes down to where people are willing to live. Builders aren't going to build somewhere that they're not," Wolf said.